This is an extract from our recent White Paper: Legal Aspects of Data – Rights and Duties, which is primarily aimed at in-house legal counsel lawyering their organisations’ data estate and data operations.

The start point for the discussion about a legal framework for data is to ask: what is the nature of information and data? For the purposes of this post, information is that which informs and either is expressed or conveyed as the content of a message or arises through common observation; and data is digital information. In the language of the standards world[1]:

“information (in information processing) is knowledge concerning objects, such as facts, events, things, processes, or ideas, including concepts, that within a certain context has a particular meaning; [and] data is a reinterpretable representation of information in a formalized manner suitable for communication, interpretation, or processing [which] can be processed by humans or by automatic means.”

Information and data as expression and communication are non-rivalrous (i.e. can be used time and again without lessening value) and boundaryless and it would be reasonable to suppose that subjecting information to legal rules about ownership would be incompatible with its nature as without limit. Yet data as digital information is only available because of investment in IT, just as music, books and films require investment in creative effort. To give a bit more colour, it may be helpful to overview some of the types of data we’re talking about before exploring the legal aspects.

What types of data are we talking about?

The types of data that in-house counsel are likely to be involved with in advising on data projects include AI datasets; big data; derived data; foundation models, LLMs (large language models) and generative AI; linked data; metadata; open data; Smart Data; real-time, delayed and reference data; and structured and unstructured data.

The equivocal position of data as non-rivalrous and boundaryless but only available as a result of investment in IT is reflected in the start point for the legal analysis, which is that data is elusive stuff in legal terms. This is best explained by saying ‘there are no rights in data but that rights and duties arise in relation to data’. The 1979 UK criminal law case of Oxford v Moss is authority that there is no property in data as it cannot be stolen; and a 2014 UK Court of Appeal (‘CoA’) case confirmed that a lien (a right entitling a person with possession to retain it in certain cases) does not subsist over a database.[2] However, the legal rights and duties that arise in relation to data are both valuable and potentially onerous and, as an area of law, developing particularly rapidly at the moment

These rights and duties arise through IP, contract and regulation. They are important as (positively, in the case of IP and contract) they can increasingly be monetised and (negatively) breach can give rise to extensive damages and other remedies (for IP infringement and breach of contract) and fines and other sanctions (breach of regulatory duty).[3] Current developments in each of these areas mean that ‘data law’ has emerged as a new area in its own right around IP, contract and regulation.

Towards a common legal framework for data: the 8 layer stack

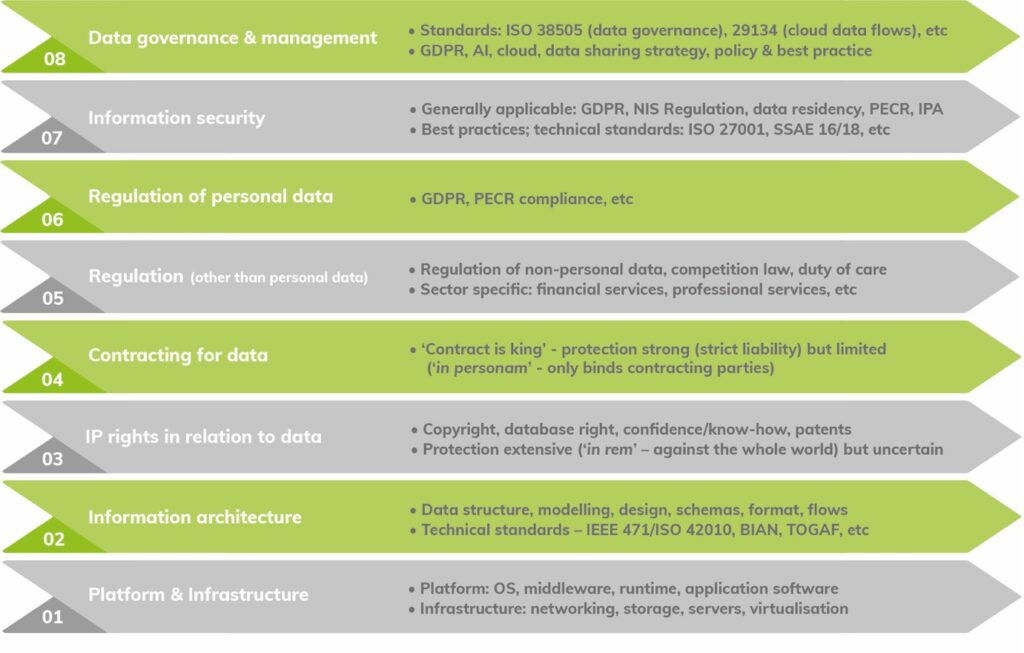

IP, contract and regulation in the context of data can be conceptualised in a legal model as the middle four layers in an eight layer stack, sandwiched between platform infrastructure and information architecture below and information security and data management above

This is an extract from Richard Kemp’s recent White Paper: Legal Aspects of Data – Rights and Duties. You can download the full white paper here.

[1] See ISO/IEC (the International Organization for Standardization/the international Electrotechnical Commission) standard 2382-1: 1993(en), Information Technology – Vocabulary. See https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-iec:2382:-1:ed-3:v1:en. Information and data are used interchangeably in this paper.

[2] Your Response Ltd v Datateam Business Media Ltd, judgment of the CA on 14 March 2014 [2014] EWCA 281; [2014] WLR(D) 131. See http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2014/281.html. A lien in UK law is a possessory remedy available for a ‘thing’ (or ‘chose’) in possession – as personal tangible property. A database however is a ‘thing’ (or ‘chose’) in action – capable of enjoyment (or enforcement) only through legal action. The is not authority that that there is no property at all in a database, just that there is no personal tangible property.

[3] For a more detailed review of data law see Kemp et al, ‘Legal Rights in Data’ (27 CLSR [2], pp. 139-151).