The UK CMA’s Review of Foundation Models

The UK Competition and Markets Authority (‘CMA’) recently announced a review of AI foundation models[1] as part of its implementation of the UK Government’s approach to AI regulation.[2] The review is focusing on barriers to entry in the development of foundation models, their impact on other markets, and consumer protection. The CMA’s review is an early and timely intervention in a high impact transformative technology.

Compliance with intellectual property laws and the potential impacts on IPR holders are outside the scope of the CMA’s review, but recent developments in the US are starting to show how things may play out in the UK and Europe.

What are Foundation Models?

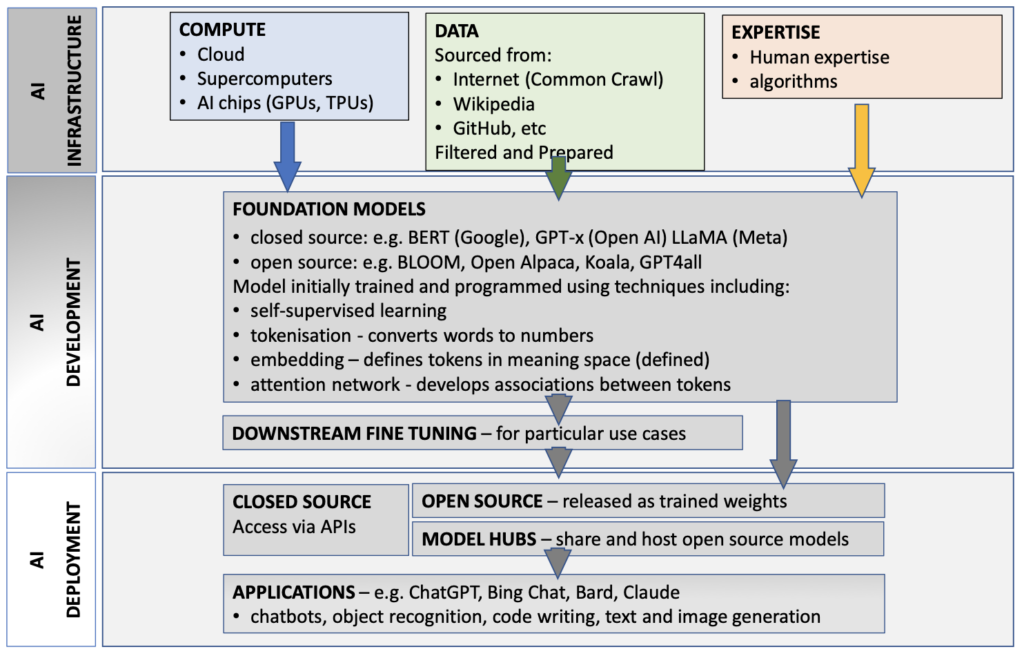

Foundation models depend on vast amounts of raw data, the algorithms to harness and train them, and powerful computing capabilities (in the shape of graphics (GPUs) and tensor (TPUs) processing units). The raw data is typically taken from the internet – for ChatGPT-3 it was sourced from snapshots of the whole internet between 2016 and 2019 by Common Crawl, a web crawler. The raw data is cleaned up and trained using ‘self-supervision’. This removes the need for the underlying data to be labelled and enables the system to learn by itself, massively speeding things up.

Foundation Models[3]

The foundation model then undergoes a number of processes (see the graphic above), all happening many times over in parallel to speed things up even further. As the CMA initial review explains:

“During training, the data is broken down into small tokens (for example text data can be broken down into words) and the model learns the probabilistic relationships between each token and every other token in the data it is provided”. (page 4)

In a bit more detail:[4]

- first, the underlying data is converted into numerical tokens;

- next, the token is given a definition and embedded into a ‘meaning space’ near other tokens with similar meanings;

- third, the system’s ‘attention network’ then develops associations between the tokens over billions of training runs;

- fourth, the system gradually codes as weights what it sees as numbers and uses these weights to make the token associations closer and more accurate;

- fifth, the model is fine tuned for particular use cases; and

- finally, the application is deployed – for example as chat or generative, code writing or image generation.

Foundation Models and Intellectual Property – the US

Much of the content of foundation models is potentially copyrightable and regulatory intervention and litigation are to be expected establishing the borders of what is, and what is not, protectible or infringing.

In March 2023, the US Copyright Office[5] gave clear guidance on how to deal with works containing material generated by AI, stating:

“If a work’s traditional elements of authorship were produced by a machine, the work lacks human authorship and the Office will not register it. This includes situations where an AI technology is developed such that it generates material autonomously without human involvement. For example, when an AI technology receives solely a prompt from a human and produces complex written, visual, or musical works in response, the ‘‘traditional elements of authorship’’ are determined and executed by the technology—not the human user.”

An early case in the US is Getty Images v Stability AI.[6] Here Stability AI created an image generation model called Stable Diffusion which uses AI to deliver ‘computer synthesized’ images in response to text prompts. Getty, in its 29 March 2023 amended complaint, alleges that Stability AI has copied over 12 million Getty Images photographs in infringement of Getty’s copyright, trademarks, goodwill and website terms of use.

A case that maybe raises more questions is a class action brought against co-defendants GitHub, Microsoft and OpenAI[7] alleging copyright infringement in enabling Copilot, a code generation model trained on billions of lines of code, to serve up licensed code snippets without credit. The defendants contend that the case should be thrown out on pretty much all counts – that the claimants have failed to show that copyright has arisen; that they own the copyright; that the defendants have infringed the copyright; or that the plaintiffs have suffered any loss.

Foundation Models and Intellectual Property – the UK

How these cases progress will be of interest to lawyers advising on AI everywhere. And what about the UK? Here are our top ten points:

- Computer-generated works: the UK’s approach to computer-generated works differs from the US. Under s.9(3) of the UK Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1998[8] the author of a computer-generated work is the person who undertook the arrangements for its creation; and by s.178, a computer-generated work is a work generated by computer where there is no human author of the work. So it looks like you can trace back in the UK to a human in the loop in a way that you can’t in the US.

- Screen scraping: very often parts of the foundation model are created through web crawling and screen scraping. Many websites’ terms of use seek to bar this kind of activity, and both the Stability and Copilot cases include breach of contract claims.

- Foundation model operator terms of licence / service: these need to be reviewed carefully by corporate users as they contain traps for the unwary, particularly in the areas of data protection, confidentiality, indemnification, liability, scope of licence and ownership of data and derived data.

- Text and data mining: the EU has adopted the text and data mining (‘TDM’) exception in the Digital Single Market Directive. [9] This covers “any automated analytical technique aimed at analysing text and data in digital form in order to generate information which includes but is not limited to patterns, trends and correlations”. The exception may be overridden by appropriately expressed reservation language. The UK did not enact the Directive before Brexit and there has been much discussion about the scope of the TDM exception: where it will land here is still an open question.

- UK ‘permitted act’ copyright exceptions: outside the TDM exception, the UK does not have the broad US ‘fair dealing’ copyright exception, and defendants may struggle to shoehorn foundation models into one of the more specific UK permitted acts.

- Database right: database right is particular to UK and EU law. A plaintiff may be able to claim that a foundation model creator has extracted or re-used the contents of the plaintiff’s database, but national courts in Europe and the European Court of Justice have not been overly sympathetic to database right infringement claims. Somewhat counterintuitively, it may be easier for the foundation model operator to claim database right in the model they have created.

- Publishing summaries of copyright material used to train AI models: The European Parliament has recently proposed amending the drat AI Act to require generative foundation model operators to publish summaries of copyright material used for training.

- Copyright in input queries and output responses, etc: Finally, watch the IP position in relation to input queries and output responses generated from those queries.

- Other IP: consider other IP like trade secrets, trade marks and rights to inventions.

- Data protection, etc: IP is just one of a number of legal areas impacted by AI – in particular, don’t forget data protection.

As ever, the law struggles to keep up with the tech – but with AI foundation models, the pace of tech change is faster and the range of legal issues impacted broader than anything we’ve seen before.

Endnotes

[1] AI Foundation Models: Initial review (publishing.service.gov.uk), CMA, 4 May 2023

[2] A pro-innovation approach to AI regulation – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk), Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, 29 March 2023

[3] Source: CMA Initial Review, page 8 (as adapted)

[4] For two good backgrounders see Large, creative AI models will transform lives and labour markets | The Economist, 22 April 2023 and Big Tech is racing to claim its share of the generative AI market | Financial Times, 20 April 2023

[5] Federal Register :: Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, US Copyright Office, 16 March 2023

[6] Getty Images (US) Inc. v Stability AI, Ltd and Stability AI, Inc., Amended Complaint of 29 March 2023, gov.uscourts.ded.81407.13.0.pdf (courtlistener.com)

[7] Individual and Representative Plaintiffs v GITHUB, Inc, Notice of Motions and Motions to Dismiss, Microsoft and GitHub Motion to Dismiss – DocumentCloud, 26 January 2023; Plaintiffs v GitHub, Inc, Microsoft Corporation, OpenAI, Inc etc, Notice of Motion and Motion to Dismiss Complaint, 26 January 2023, OpenAI Motion to Dismiss – DocumentCloud

[8] Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (legislation.gov.uk)

[9] Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council Of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directive 96/9 and 2001/29 – https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32019L0790&from=EN.