Rarely as we leave one year behind has the outlook for the next been shrouded in such uncertainty. Whether stemming from Brexit or politics (in the UK) or China, climate, Covid, cyclical slowdown, inflation or Ukraine (in the world at large), 2023 looks like it’s going to be different.

The macro tech development trends of 2023 remain those of the of the last few years: cloud, artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), 5G, blockchain, digital assets, digital payments, the virtual world and its convergence with the physical. These trends will continue to intensify and amplify in 2023 in a world of recalibrating valuations for big tech and not-so-big tech[1].

And it’s this combination of uncertainty, intensity and complexity that makes 2023’s tech picture trickier than usual to foresee. What does all this mean for tech lawyers in 2023?

Managing data continues to preoccupy business at every level. In a recent survey, data platform provider Splunk[2] found that 67% of data innovation leaders considered that their data was growing more quickly than their ability to keep up. That fact has not stopped businesses looking for ways to exploit their data to improve business processes, services, and customer and staff satisfaction as the desire to “unlock” data for analytics continues to be a driving factor in digital transformation projects.

The cloud sets the stage for everything else. Turning raw data into AI that can understand context and the world fuels the intelligent cloud (remote but distant) and the intelligent edge (remote but local) at each level of infrastructure, platform and software. These developments are behind the current (and still) dramatic increases in the sheer power and reach of computing. These in turn drive digital transformation and innovation which, in a virtuous circle, accelerate cloud uptake.

The development of AI capabilities – ‘everywhere and nowhere’ – is pivotal to these trends. Advancing virtual, mixed and augmented realities herald the arrival of the metaverse, currently at the threshold of mainstream adoption in both the business space and for the consumer. A bit like the internet at the turn of the century, how the metaverse will develop is not yet clear. What is clear is that we are at a point where a range of AI-driven spatial technologies in the fields of location and context awareness, reality capture, design and visualisation and augmented, mixed and virtual reality are maturing at roughly the same time. One possibility is that separate digital environments will build out as new infrastructure layers on top of the internet and coalesce around persistent (mass market) or temporary (smaller group) metaverses that leverage these technologies. Potential examples here include film metaverses (driven by innovation in computer graphics and virtual production) and technical metaverses (driven by innovation in digital twinning as 3D models of physical world environments). NFTs (non-fungible tokens), digital assets, low-code, blockchain and digital payments are now increasingly well established as critical enabling technologies for the digital world.

All these developments generate new business dynamics, with new contractual approaches following hard on their heels. Whilst cloud contracting terms at all levels are increasingly mainstream, new business patterns around data, AI, digital worlds, blockchain, digital assets and payments will keep lawyers busy crafting new contract models in 2023.

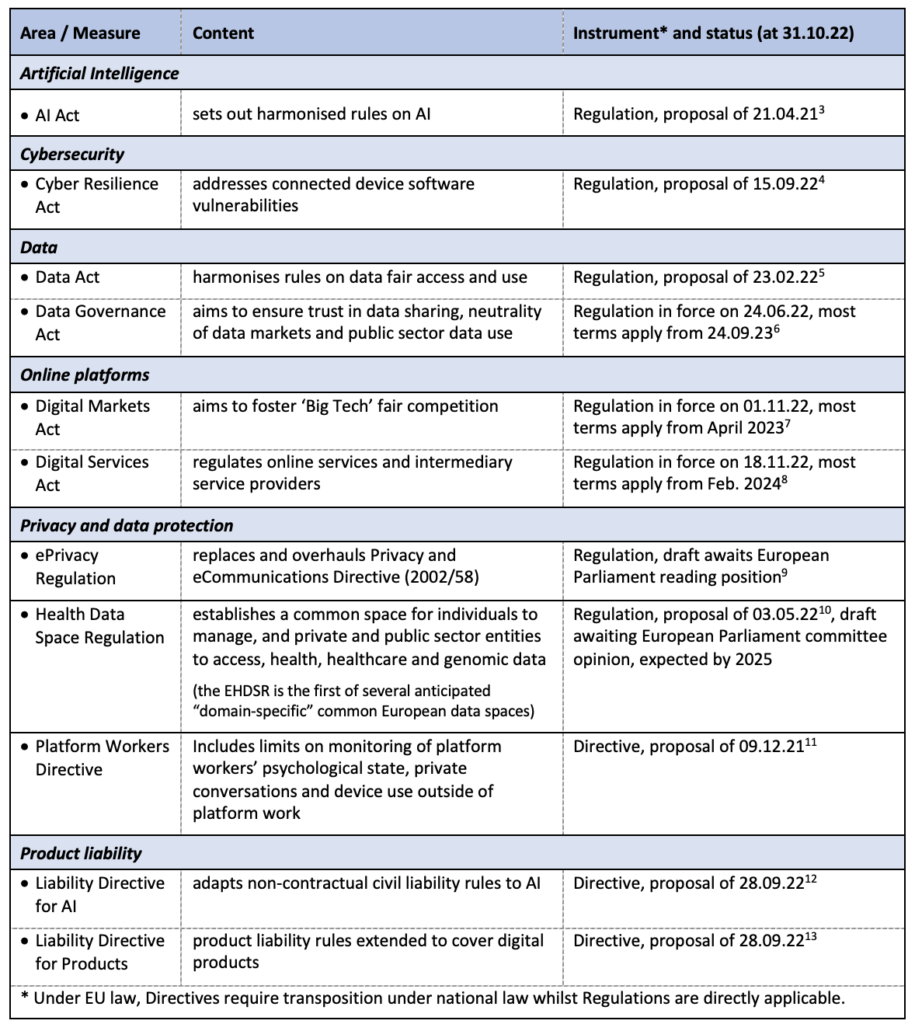

Regulatory response – the EU’s tech rule toolbox

The development of these technologies has drawn a full-on regulatory response, most notably in the EU’s comprehensive Digital Strategy and Policy Programme. Remarkably, the start of 2023 sees no fewer than ten major new sets of rules proposed, in transition or in force. Covering AI, cybersecurity, data, platforms, ePrivacy (still!), healthcare and workforce data and product liability (see the table below), this extended toolbox of new rules represents the most complete and vigorous policy response to the demands of technology change yet seen anywhere.

This new ‘rule box’ is extremely broad, but devils lurk in the detail– a possible maximum 30 day notice period for terminating cloud contracts in the Data Act is a case in point.

How the GDPR has played out since 2018 within the EU and around the world may offer some insight as to the operation of the new rules, most of which will fully apply by the end of 2024. Within the EU and as the legislation moves from agreeing to implementing the rule box, the hope must be that it will be implemented more consistently than the GDPR, where enforcement standards increasingly diverge within the bloc. As with GDPR, will the EU’s approach be followed elsewhere? In particular, if (as seems likely) the US follows an industry sector-based approach, will this lead to the sorts of tensions we have seen following Schrems II[14] in the area of data protection?

The UK

And what of the UK? UK institutions are still grappling with the consequences of Brexit for tech – examples include the approach of the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) to exhaustion of IP rights and the interplay between AI and IP (where HMG in June 2022 indicated that it would introduce a new mandatory copyright exception for text and data mining)[15].

In the EU Withdrawal (Revocation and Reform) Bill 2022, the Truss administration proposed sunsetting at the end of 2023 all pre-Brexit EU law that have not been expressly continued in UK law by then.[16] Many civil servants and MPs across the political spectrum, including leading Brexiteers, have expressed alarm at the resources such a review would require, and as we head into 2023 it remains to be seen whether this policy will survive contact with reality. If it does, the bonfire of Brussels-based rules will add another layer of complexity to advising on UK regulation.

The lack of continuity in the Conservative administrations in 2022 has hampered development of key domestic legislation (like the Online Safety Bill) and policy (like data protection reform). How HMG will push ahead with online safety will be a key theme for 2023; as will be the balance to be struck between the GDPR’s reach and HMG’s stated aim of reducing the privacy burden on business. The future of the UK/EU Adequacy Decision[17], due anyway to expire on 27 June 2025 unless extended, is likely to be a point of increasing pressure in striking this balance. Recent commentary from DCMS on the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill indicates a shifted focus to preserving adequacy, and a new consultation for private and civil society groups is anticipated over the coming weeks[18]. However, whether that “public” position on adequacy is carrying through within Whitehall is unclear. European Parliament MEPs who travelled to the UK in early November to discuss the UK’s proposed reforms reported feeling “taken for fools” as MPs and the ICO official seemed ill-prepared, stressed “growth and innovation [but] nothing about human rights” and were “giving in on privacy in exchange for business gain”[19].

Meanwhile in September, UK competition regulator the CMA (Competition and Markets Authority) announced it was launching a Phase 2 in depth investigation into Microsoft’s planned acquisition of Activision Blizzard under the merger control provisions of the Enterprise Act 2002[20]. Also in September 2022 and under the Enterprise Act, UK communications regulator Ofcom opened a market study examining the positions of Amazon, Google and Microsoft in the £15bn UK cloud market.[21] The results of both the investigation and the market study will be published in 2023.

Data protection – other key developments

The EU and UK data protection authorities (“DPAs”) will likely have a number of other similar priorities over 2023:

- Workforce monitoring – including the ICO’s consultation on its updated monitoring at work guidance[22], and limits on monitoring under the draft EU Platform Workers’ Directive[23];

- Other biometric monitoring, including facial recognition and emotion detection – facial recognition business Clearview’s appeal of its UK ICO fine, and what happens regarding its EU DPA fines[24], will be important viewing for similar vendors and other third country actors who may be brought within GDPR by Article 3;

- AdTech and cookies – including the outcome of the appeals by Experian and IAB Europe on enforcement action by the ICO[25] and Belgian DPA[26], respectively;

- Continued thought on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) and encryption – including the ICO’s PETs consultation[27], and the ongoing debates on encryption backdoors and device scanning; and

- (Responsible) use of health, healthcare and genomics data – as thrown into the spotlight by the pandemic – including, the new EU Health Data Spaces Regulation[28], and HMG’s pro-innovation agenda.

The EU and the UK are also likely to pursue further individual priorities.

In the EU, a shift likely to continue from 2022 into 2023 is greater enforcement activity by EU DPAs – flowing from:

- a perceived lower threshold for complaints following the flood of Google Analytics actions;

- persistent reliance by EU public institutions on US cloud service providers;

- DPAs frustrated at the slow Irish DPC, bypassing the “one-stop-shop” mechanism to take direct action against Big Tech; and

- the role of the Data Protection Officer (DPO) – a priority for the EDPB – in particular those DPOs also performing other business functions, such as CISOs, CEOs, CFOs, that affect their independence.

Meanwhile the UK is unlikely to follow in the EU’s steps on international transfer enforcement – although the Information Commissioner, John Edwards, has been taking a more proactive approach on other matters, e.g. the £4.4 million fine against construction company, Interserve Group Limited[29], and the production of guidance videos and tutorials to alleviate the training cost burden. The ICO will also continue its return to a “business-as-usual” guidance review to refresh the bank of pre-GDPR guidance, including on direct marketing and employment practices.

A radical new legal basis for digital assets?

Perhaps the most notable UK development in 2022 was the Law Commission’s consultation paper on Digital Assets published in July,[30] building on the November 2019 Lawtech Delivery Panel’s Legal Statement on Cryptoassets and Smart Contracts.[31] The paper contains a powerful analysis of information and property rights and, in a low key but potentially far-reaching way, proposes a new kind of property for consultation.

UK law traditionally recognises two types of personal property – ‘things in possession’ (goods and other tangible things) and ‘things in action’ (intangible things like debts, contract claims and intellectual property that ultimately you can only assert through legal action).

The Law Commission proposes the ‘data object’ as a new, third type of personal property where it:

- consists of data represented in an electronic medium;

- exists ‘there in the world’, independently of any particular person and the legal system (so a thing in action couldn’t be a data object); and

- is ‘rivalrous’ (i.e. its capacity for use is not unlimited – ‘if I have it, you can’t’).

The paper then explores how these criteria might or might not apply to particular kinds of assets like digital files, email accounts, in-game digital assets, domain names, carbon emission schemes, crypto-tokens and NFTs. It then suggests how data objects could fit within existing legal concepts and principles as to creation, transfer of legal and equitable interests, security interests, custody, causes of action and remedies.

NFTs: ‘the map is not the territory’[32]

NFTs have attracted much media attention recently, particularly in the art and luxury goods worlds, and the Law Commission paper devotes a chapter to them. The starting point is that, as an individually identifiable, cryptographically enabled token, an NFT can meet the criteria for a data object. It is in the link between that NFT and something else (for example, a drawing or image in digital form as a dataset external to the NFT’s dataset) that challenging questions around permissioning, ownership and control can arise, especially where the NFT’s contractual terms of use impact the legal rights in that something else.

More technically from the legal perspective, there may well be property rights in both the internal dataset of the NFT and the external dataset that it links to; and whether, and if so how, the terms of use that apply to the NFT holder seek to confer rights or impose duties on the linked external dataset and its owner can then become critical.

Say an architect as creator mints (registers on a blockchain) an NFT of their building drawings and invites metaverse builders to license them and construct the architect’s building in the builder’s virtual world. Here, the positions of, and relationships between (on the one hand) the NFT and drawings (as assets) and (on the other) between creator, NFT holder and builder will require careful consideration in contractual, property and IP terms. Although there are few publicly available licences in this area, an NFT Licence published by community NFT market-place operator Rarible is a useful precedent for contractual terms,[33] but as the Law Commission sums up (at paragraph 15.61):

“Given that the NFT market remains in its infancy, we expect that further innovation from creators, developers, legal engineers and lawyers will help to explore the various possible uses of the technology. This could significantly alter how creators interact with digital rights management in future.”

The metaverse in 2023

In a great piece from mid-2022, ‘You Don’t Want What You Think You Want – AI and Procedurally Generated Worlds’,[34] tech strategist Daniel Faggella shows us how AI, the metaverse (as a ‘procedurally generated world’) and other emerging technologies may open up new means to the fulfilment of human needs in the next 10 to 15 years.

As ever, legal approaches will evolve to follow the new business patterns of these new worlds, but as can be seen from the commentary above, law and regulation is beginning – in some jurisdictions at least – to catch-up with the technology to begin to exercise more control over various aspects of life with/in the metaverse. The world of contractual relationships underpinning the metaverse is rapidly being supplemented with new jurisdiction specific rules on everything from AI to data to NFTs. These rules pose an additional challenge for the metaverse and we expect to see some changes in how platforms develop and operate as these rules are introduced over time.

Without necessarily wishing to look that far ahead, it’s clear from the debate around the ‘legals’ of NFTs for example that the digital environment will test and stretch established legal norms. We’ll see this particularly in the areas of insolvency law (the first place where novel legal constructs hit reality), intellectual property, contract and regulation. A lot of this is further out than 2023, but particularly in the enterprise space, we’re starting to see what this means for digital twins and augmented and mixed reality already.

Interoperability among metaverse platforms and technologies is now a common aim, critical to unlocking value for users and businesses alike. Some form of cross-platform/technology/metaverse interoperability will be required to enable users to e.g. port digital assets from 1 metaverse to another. 2022 saw the establishment of the Metaverse Standards Forum[35] (MSF), an independent organisation whose aim is to “encourage and enable the timely development of open interoperability standards essential to an open and inclusive” metaverse. Its intention is to work with businesses and standard organisations to co-ordinate requirements and support for the development of new, metaverse specific standards. At the time of writing, the MSF has over 1800 members and we expect to see those numbers increase as it begins its work in earnest in 2023 and beyond. The task it sets itself is not an easy one given the multitude of technologies, rights and interests to be taken into account, but we believe it is a positive development in opening discussions and enabling different interested parties to discuss the issue together, without any obligations to license IP or disclose confidential know-how or data.

Richard Kemp, Deirdre Moynihan, Chris Kemp, Eleanor Hobson

Kemp IT Law LLP, London

November 2022

[1] What went wrong with Snap, Netflix and Uber? | The Economist (31 October 2022)

[2] Splunk Inc., <The Economic Impact of Data Innovation 2023 (splunk.com)>, (October 2022)

[3] European Commission, AI Act Proposal [COM(2021)206 final] (21 April 2021) <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0206&from=EN>.

[4] European Commission, Cyber Resilience Act Proposal [COM(2022)454 final]

<https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022PC0454&from=EN>.

[5] European Commission, Data Act Proposal [COM(2022)68 final] <1_EN_ACT_part1_v8.docx (europa.eu)>.

[6] Regulation 2022/868 of 30 May 2022, Data Governance Act <L_2022152EN.01000101.xml (europa.eu)>.

[7] Regulation 2022/1925 of 14 September 2022, Digital Markets Act <L_2022265EN.01000101.xml (europa.eu)>.

[8] Regulation 2022/2065 of 19 October 2022, Digital Services Act <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2022:277:FULL&from=EN&pk_campaign=todays_OJ&pk_source=EURLEX&pk_medium=TW&pk_keyword=Digital%20service%20act&pk_content=Regulation%20>, pp.3-104.

[9] European Commission, 2017 ePrivacy Regulation Proposal [COM(2017)10 final] <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017PC0010&from=EN>.

[10] European Commission, European Health Data Space Proposal [COM(2022)197 final] <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0197>.

[11] European Commission, Improving Working Conditions in platform work proposal [COM(2021)762 final] < https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=24992&langId=en>

[12] European Commission, AI Liability Directive Proposal [COM(2022)496 final] <1_1_197605_prop_dir_ai_en.pdf (europa.eu)>.

[13] European Commission, Product Liability Directive Proposal [COM(2022)495 final] <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022PC0495&from=EN>.

[14] Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Limited and Schrems, Case C-311/18 <CURIA – List of results (europa.eu)>.

[15] IPO, Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: copyright and patents: Government response to consultation (28 June 2022)<Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: copyright and patents: Government response to consultation – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)>.

[16] HMG, The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill 2022 (22 September 2022) <The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill 2022 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)>.

[17] Commission Implementing Decision of 28 June 2021 <https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/decision_on_the_adequate_protection_of_personal_data_by_the_united_kingdom_-_general_data_protection_regulation_en.pdf>.

[18] See, for example, comments from the Westminster eForum (1 November 2022) reported at: < Data Protection Bill: Consultation to delay UK GDPR replacement (techmonitor.ai)>

[19] Vincent Manancourt, Politico, ‘We were taken for fools’: MEPs fume at UK data protection snub (7 November 2022) <‘We were taken for fools’: MEPs fume at UK data protection snub – POLITICO>

[20] HMG, Microsoft / Activision deal could lead to competition concerns (1 September 2022) <Microsoft / Activision deal could lead to competition concerns – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)>.

[21] Ofcom, Ofcom to probe cloud, messenger and smart-device markets (22 September 2022)<Ofcom to probe cloud, messenger and smart-device markets – Ofcom>.

[22] ICO consultation on the draft employment practices: monitoring at work guidance and draft impact assessment (12 October 2022) < ICO consultation on the draft employment practices: monitoring at work guidance and draft impact assessment | ICO>

[23] See fn at table above.

[24] See, for example: the French CNIL (20 October 2022) <Facial recognition: 20 million euros penalty against CLEARVIEW AI | CNIL>; the Hellenic DPA (13 July 2022) <Επιβολή προστίμου στην εταιρεία Clearview AI, Inc | Αρχή Προστασίας Δεδομένων Προσωπικού Χαρακτήρα (dpa.gr)>; and the Italian Garante (10 February 2022) < https://www.garanteprivacy.it/home/docweb/-/docweb-display/docweb/9751323>.

[25] See ICO enforcement notice at: <Experian limited enforcement report (ico.org.uk)>

[26] See Belgian DPA press release at: < The BE DPA to restore order to the online advertising industry: IAB Europe held responsible for a mechanism that infringes the GDPR | Autorité de protection des données<br>Gegevensbeschermingsautoriteit (dataprotectionauthority.be)>

[27] ICO consultation on Anonymisation, pseudonymisation and privacy enhancing technologies guidance (7 September 2022) <ICO call for views: Anonymisation, pseudonymisation and privacy enhancing technologies guidance | ICO>

[28] See fn at table above.

[29] See Enforcement Notice at: < Interserve Group Limited | ICO>

[30] Law Commission, Digital Assets: Consultation Paper (28 July 2022) <Law Commission Documents Template>.

[31] LawTech Delivery Panel, Legal statement on cryptoassets and smart contracts (Nov 2019) <LawtechUK Resources (technation.io)>.

[32] Law Commission, Digital Assets: Consultation Paper, para 15.39, p.318, attributed to Mr Gabriel Shapiro.

[33] <https://github.com/rarible/nft-license> licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

[34] Daniel Faggella, Head of Research, Emerj (11 August 2022) <You Don’t Want What You Think You Want – AI and Procedurally Generated Worlds | Emerj Artificial Intelligence Research>.

[35] https://metaverse-standards.org/